- Emily of New Moon is a relatively rare example of a female künstlerroman--novel of an artist's development. Detail how L.M. Montgomery represents the development using a specific narrative form: i.e. the epic quest. You may refer to the autobiographical aspect of the text in your essay.

- We learned in lecture how Kingsley Amis choses very specific words to diminish the masculine aspect of the fight between Bertrand Welsh and Jim Dixon in Lucky Jim. By close reading, show how Amis uses exact words to depict Jim at any two moments of successful masculine performance and in any two scenes of failed masculinity.

- The portrait of Flora Poste in Cold Comfort Farm is evidently a model of the New Woman: independent, assertive, socially liberated and in charge. That is, so long as the reader is oblivious to, or choses to ignore, Stella Gibbons sophisticated satire. In your essay, make Gibbon's exquisite satire plain to such a reader.

Wednesday, September 30, 2009

Mid-Term Essay Topics

Chose your topic for the mid-term esssay from the following three.You will need, for your choice, to formulate a strong thesis statement, using, ideally, the conceptions and techniques preseneted in lecture.

Epic Quest

A useful webpage for understamding the aspect of the epic quest -- the 'hero's journey -- is this illustrative use of The Matrix and Star Wars. More pedestrian but straightforward is at this link.

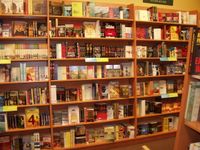

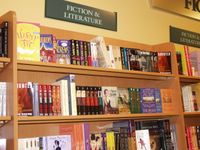

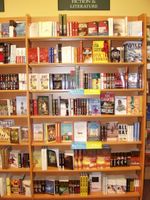

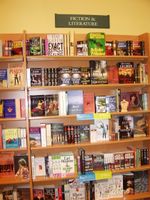

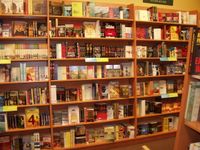

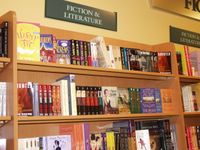

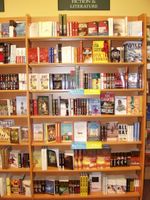

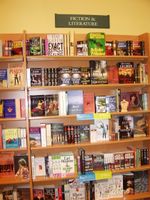

Chick-Lit Prominence in BookStores

To show how prominently Chick-Lit is market displayed, I took these pictures in the Lougheed Mall Coles Books. Click on the individual pictures for a larger image.

Here is the Lougheed Mall Coles Books' courteous and professional store manager, Ms. Lori Drazdoff, beside a sub-display of various fiction titles marketed to women.

Following are pictures are of several sections of the "Fiction & Literature" shelves that run along the main walls. The books marketed as chick-lit are clear: their covers are in bold pastels frequently with variations on retro-sixties movie-style line-drawings. My assumption is that the marketers are invoking the iconography of Breakfast at Tiffany's.

In addition to the covers, books marketed as chick-lit have titles that strongly declare their genre. Here, Mary Kay Andrews' Hissy Fit typifies the genre's reformative appropriation of idioms hitherto applied in the feminine pejorative.

Here is the Lougheed Mall Coles Books' courteous and professional store manager, Ms. Lori Drazdoff, beside a sub-display of various fiction titles marketed to women.

Following are pictures are of several sections of the "Fiction & Literature" shelves that run along the main walls. The books marketed as chick-lit are clear: their covers are in bold pastels frequently with variations on retro-sixties movie-style line-drawings. My assumption is that the marketers are invoking the iconography of Breakfast at Tiffany's.

In addition to the covers, books marketed as chick-lit have titles that strongly declare their genre. Here, Mary Kay Andrews' Hissy Fit typifies the genre's reformative appropriation of idioms hitherto applied in the feminine pejorative.

British Class System

I noted in lecture that North Americans are prone to some misunderstandings when reading British fiction due to a lack of awareness of the almost universal effects of the class system there. This, you will discover, is an essential -- arguably, by far the most significant -- aspect of the cultural background to British literature of the 19th & 20th Centuries.

Let me elaborate here. First, a former student's working class father (clearly a highly admirable man) earned Cambridge in the nineteen fifties, by which time the class boundaries were feeling the blows of many engines: the two World Wars for instance. And second, at a larger remove, remember that Britain has a system of class not caste: in other words, there had always been some opportunity for mobility - in both directions. Profligate aristocrats had for centuries dropped their posterity well into the middle class. Successful business acumen brought some middle (and even some originally lower) class men into the aristocracy via a knighthood. Consider Sir William Lucas in Pride and Prejudice. And elevation by marriage was also an avenue: the stage was an effective platform in more than one sense; and "let a man be ordained to the clergy and he can marry as high as he likes" is a line from Born in Exile by George Gissing.

But beside all this, mobility is only one aspect of the class system: the levels are enduringly divided by the behavior and attitudes that the members of each level share. Mr. Lucas could rise to status of gentlemen, but he could not prevent Mr. Bingley's sisters from sneering at him behind his back. Indeed, only Elizabeth Bennett's omnipotent womanhood could make Mr. Darcy repent (with obsequy) of his disdain for her Cheapside relations, the Gardners.

My point about North America is that culture is uniform to a degree not experienced in England. Members of the Canadian Senate watch NHL games in undershirts while drinking beer - as does a longshoreman in Surrey whose choice of beer is quite likely to be Stella Artois. During the last American Presidential election, John Kerry -- a north-eastern aristocrat -- rode a mountain bike, wore a trendy yellow Lance Armstrong bracelet and had rap on his iPod. Bank balances allow for important -- even critical -- differences in health and opportunity among North Americans. And ethnic diversity provides reasons to celebrate significant difference. But for all that, a remarkable similarity of taste and value makes "class" a problematic term to apply. The "Red State/Blue State" divide, for instance, is a geographic and regional divide, not a class divide. And the rural/urban divide in Canada does not map faciley to income.

Less so under New-Labour Britain (which is just what is argued as a master hypothesis by this course,) but still very much alive, is exactly a class distinction where North America has a conformity. It was the fact that Diana: Princess of Wales, behaved like Anna Nicole Smith that caused Her Unstable Highness to be ostracised by the British aristocracy. And, contrariwise, the fox-hunting passion of aristocrats -- nouveau and old alike -- produces derision against "toffs" from the man on Wigan pier.

Speaking of George Orwell, here is one of his many characteristically pithy insights into the British class differences in terms of attitude rather than mobility.

style="font-size: small;">The class system (aristocratic, bourgeois, and lower classes) is, as mentioned, the vestige of the feudal system of noble, yeoman, serf. And thus it is a system based on wealth: finance correlates with class, but does not determine it. Indeed, to talk of wealth as class marker is to commit the solecism of elevating the value of one class -- the bourgeois -- to supremacy. North Americans do use "upper," "middle" and "lower" as synonyms for "Rich, average, and poor," but that is because North America simply is a bourgois continent. Moreover, making "weath" equal to "money" is more of the triumph of the bourgeoise; since turning worth into capital was the strategy of the Whigs .... and the means by which they effected their conquest.

Here is George Gissing to this end -- and bear in mind as you read this passage from the "Summer" section of The Private Papers of Henry Ryecroft that Gissing is widely touted as being the pre-eminent novelist of the Reformers:

The destruction of the class system in England is, then, the destruction of the aristiocracy and the lower class by the bourgeois: the former they tore down to their level from resentment & envy; the latter they pulled up by sheer condescention.

Let me elaborate here. First, a former student's working class father (clearly a highly admirable man) earned Cambridge in the nineteen fifties, by which time the class boundaries were feeling the blows of many engines: the two World Wars for instance. And second, at a larger remove, remember that Britain has a system of class not caste: in other words, there had always been some opportunity for mobility - in both directions. Profligate aristocrats had for centuries dropped their posterity well into the middle class. Successful business acumen brought some middle (and even some originally lower) class men into the aristocracy via a knighthood. Consider Sir William Lucas in Pride and Prejudice. And elevation by marriage was also an avenue: the stage was an effective platform in more than one sense; and "let a man be ordained to the clergy and he can marry as high as he likes" is a line from Born in Exile by George Gissing.

But beside all this, mobility is only one aspect of the class system: the levels are enduringly divided by the behavior and attitudes that the members of each level share. Mr. Lucas could rise to status of gentlemen, but he could not prevent Mr. Bingley's sisters from sneering at him behind his back. Indeed, only Elizabeth Bennett's omnipotent womanhood could make Mr. Darcy repent (with obsequy) of his disdain for her Cheapside relations, the Gardners.

My point about North America is that culture is uniform to a degree not experienced in England. Members of the Canadian Senate watch NHL games in undershirts while drinking beer - as does a longshoreman in Surrey whose choice of beer is quite likely to be Stella Artois. During the last American Presidential election, John Kerry -- a north-eastern aristocrat -- rode a mountain bike, wore a trendy yellow Lance Armstrong bracelet and had rap on his iPod. Bank balances allow for important -- even critical -- differences in health and opportunity among North Americans. And ethnic diversity provides reasons to celebrate significant difference. But for all that, a remarkable similarity of taste and value makes "class" a problematic term to apply. The "Red State/Blue State" divide, for instance, is a geographic and regional divide, not a class divide. And the rural/urban divide in Canada does not map faciley to income.

Less so under New-Labour Britain (which is just what is argued as a master hypothesis by this course,) but still very much alive, is exactly a class distinction where North America has a conformity. It was the fact that Diana: Princess of Wales, behaved like Anna Nicole Smith that caused Her Unstable Highness to be ostracised by the British aristocracy. And, contrariwise, the fox-hunting passion of aristocrats -- nouveau and old alike -- produces derision against "toffs" from the man on Wigan pier.

Speaking of George Orwell, here is one of his many characteristically pithy insights into the British class differences in terms of attitude rather than mobility.

And again, take the working-class attitude towards ‘education’. How different it is from ours, and how immensely sounder! Working people often have a vague reverence for learning in others, but where ‘education’ touches their own lives they see through it and reject it by a healthy instinct. The time was when I used to lament over quite imaginary pictures of lads of fourteen dragged protesting from their lessons and set to work at dismal jobs. It seemed to me dreadful that the doom of a ‘job’ should descend upon anyone at fourteen. Of course I know now that there is not one working-class boy in a thousand who does not pine for the day when he will leave school. He wants to be doing real work, not wasting his time on ridiculous rubbish like history and geography. To the working class, the notion of staying at school till you are nearly grown-up seems merely contemptible and unmanly. The idea of a great big boy of eighteen, who ought to be bringing a pound a week home to his parents, going to school in a ridiculous uniform and even being caned for not doing his lessons! Just fancy a working-class boy of eighteen allowing himself to be caned! He is a man when the other is still a baby. Ernest Pontifex, in Samuel Butler’s Way of All Flesh, after he had had a few glimpses of real life, looked back on his public school and university education and found it a ‘sickly, debilitating debauch’. There is much in middle-class life that looks sickly and debilitating when you see it from a working-class angle.Note how this corrects the mistaken North American misunderstanding that the proletariat pines in frustrated envy for the values of the middle and upper middle classes. As an exemplary aside, I often observe students and professoriat alike stating that some group or another of fellow citizen are "deprived" of a university education: making, that is, university attendance a quality of universal worth. Too flagrantly pretentious and distastefully preening, I believe, to insist that one's own accidental preference or aptitude must be the sine qua non of social worth.

style="font-size: small;">The class system (aristocratic, bourgeois, and lower classes) is, as mentioned, the vestige of the feudal system of noble, yeoman, serf. And thus it is a system based on wealth: finance correlates with class, but does not determine it. Indeed, to talk of wealth as class marker is to commit the solecism of elevating the value of one class -- the bourgeois -- to supremacy. North Americans do use "upper," "middle" and "lower" as synonyms for "Rich, average, and poor," but that is because North America simply is a bourgois continent. Moreover, making "weath" equal to "money" is more of the triumph of the bourgeoise; since turning worth into capital was the strategy of the Whigs .... and the means by which they effected their conquest.

Here is George Gissing to this end -- and bear in mind as you read this passage from the "Summer" section of The Private Papers of Henry Ryecroft that Gissing is widely touted as being the pre-eminent novelist of the Reformers:

For a nation of this temper, the movement towards democracy is fraught with peculiar dangers. Profoundly aristocratic in his sympathies, the Englishman has always seen in the patrician class not merely a social, but a moral, superiority; the man of blue blood was to him a living representative of those potencies and virtues which made his ideal of the worthy life. Very significant is the cordial alliance from old time between nobles and people; free, proud homage on one side answering to gallant championship on the other; both classes working together in the cause of liberty. However great the sacrifices of the common folk for the maintenance of aristocratic power and splendour, they were gladly made; this was the Englishman's religion, his inborn pietas; in the depths of the dullest soul moved a perception of the ethic meaning attached to lordship. Your Lord was the privileged being endowed by descent with generous instincts, and possessed of means to show them forth in act. A poor noble was a contradiction in terms; if such a person existed, he could only be spoken of with wondering sadness, as though he were the victim of some freak of nature. The Lord was Honourable, Right Honourable; his acts, his words virtually constituted the code of honour whereby the nation lived.

In a new world beyond the ocean there grew up a new race, a scion of England, which shaped its life without regard to the principle of hereditary lordship; and in course of time this triumphant republic began to shake the ideals of the mother land. Its civilization, spite of superficial resemblances, is not English; let him who will think it superior; all one cares to say is that it has already shown in a broad picture the natural tendencies of English blood when emancipated from the old cult. Easy to understand that some there are who see nothing but evil in the influence of that vast commonwealth. If it has done us good, assuredly the fact is not yet demonstrable. In old England, democracy is a thing so alien to our traditions and rooted sentiment that the line of its progress seems hitherto a mere track of ruin. In the very word is something from which we shrink; it seems to signify nothing less than a national apostasy, a denial of the faith in which we won our glory. The democratic Englishman is, by the laws of his own nature, in parlous case; he has lost the ideal by which he guided his rude, prodigal, domineering instincts; in place of the Right Honourable, born to noble things, he has set up the mere plebs, born, more likely than not, for all manner of baseness. And, amid all his show of loud self-confidence, the man is haunted with misgiving.

The destruction of the class system in England is, then, the destruction of the aristiocracy and the lower class by the bourgeois: the former they tore down to their level from resentment & envy; the latter they pulled up by sheer condescention.

Wednesday, September 16, 2009

More for the Group Popular Culture Project

We seem to have met a cultural resonance with our course theme, as there is an intensification at present of engagement in arts and letters with the relations between men and women, with a strong focus on manhood.

- Here is a very engaging and informative diavlog on bloggingheads.tv under the heading Valley of the Dudes. The right-hand links on the page to the two foundational articles are especially valuable.

- Then there is Mr. Manners: Can a book teach you how to be a man? at Slate.com which gives a list of ten essential books to manhood.

- And not to be missed is another Slate.com article, this one titled The Most Interesting Man in the World: The star of Dos Equis' new ad campaign is too cool to shill beer. Consider, when you watch the ads, what they are saying about the performative masculinity model.

Saturday, September 12, 2009

Class Opinions on the Differences between the Sexes

I had good opinions from many of you on the issues that are coming up between the sexes.

Here is a keen one from classfellow Nicole M. on Petruchio's efforts to tame Kate:

Here is a keen one from classfellow Nicole M. on Petruchio's efforts to tame Kate:

....it stems from anxiety: He knows the power is going away and writes it as though he's giving it away, instead of it being taken from him.I look forward to more opinions from all of you as the Term progresses: you have the bar set here!

Wednesday, September 9, 2009

Illustrative Examples of the Course Concepts

Here's two obvious popular culture flotsam relevant to the course themes.

- Brief Interviews with Hideous Men, the film.

- "I'm going to try to write a chick-lit novel in real time. In less than a month. And I really need your help," the article.

- Why Women Have Sex, the book.

For Week Two

Very good to meet all of you: looks like a great semester ahead!

For next week, remember:

For next week, remember:

- Bring in your Seminar Writing Presentation written this week, accompanied by a one page justification of the quality of the writing. Use point-form: one bullet-point for each quality that you identify. (Example: "I use a thesis statement with a general and a particular half.") We will use this for a peer-to-peer evaluation.

- Hand your writing presentation and your justification page at the end of class to receive a 5/5 grade.

- Be prepared to review during class with your Group Project partner your comments on your choice of the two advertisements and write up a brief analysis to share with the class. This is the rehearsal of your Group Popular Culture Project.

Course Syllabus: 2009 version

Be up-to-date with the reading schedule and you will be ahead of lecture. Note, however, that this schedule is not a Procrustean bed : week by week, lecture will follow students' developing interests and the course dynamic. Thus will all material be covered, sublimely, by the end.

READING SCHEDULE

September : L.M. Montgomery, Emily of New Moon

Course Wk. 2: L.M. Montgomery, Emily of New Moon

Course Wk. 3: Kingsley Amis, Lucky Jim

Course Wk. 4: Kingsley Amis, Lucky Jim

Course Wk. 5: Stella Gibbons, Cold Comfort Farm

Course Wk. 6: Stella Gibbons, Cold Comfort Farm

Course Wk. 7: Anthony Burgess, A Clockwork Orange

Course Wk. 8: Anthony Burgess, A Clockwork Orange

Course Wk. 9: Helen Fielding, Bridget Jones's Diary

Course Wk. 10: Helen Fielding, Bridget Jones's Diary

Course Wk. 11: Nick Hornby, High Fidelity

Course Wk. 12: Nick Hornby, High Fidelity

Nb: “For purposes of the Class Participation Grade, attendance and punctuality in seminar and at lecture, as well as constructive contributions to discussion, are necessary conditions.

Schedule of Assignment Due Dates

(Assignments coded by colour. See separate assignment posts for details.)

Nb: There is a five percent per day late penalty for all assignments, documented medical or bereavement leave excepted. For medical exemptions, provide a letter from a physician on letterhead which declares his or her medical judgement that illness or injury prevented work on the essay.(The precise word "prevented" must be used in the letter.) The letter must cover the entire period over which the assignment was scheduled and may be verified by telephone.

September 9th, Seminar Writing Presentation #1, in-class.

September 16th: Group Project dates selected.

September 30th, Mid-Term Essay topics posted.

October 7th: Mid-Term Essay peer editing of thesis ¶ or draft outline.

October 14th: Seminar Writing Presentation #2, in-class

October 21st: Mid-Term Essay draft version due in class.

November 4th: Seminar Writing Presentation #3, in-class.

November 4th: Mid-Term Essay draft version returned with comments & conditional grade.

November 18th, Mid-Term Essay peer-editing of preliminary revision.

November 25th, Mid-Term Essay revision due in class.

December 2nd: Mid-Term Essay revision returned with summary comments & final grade

December 16th, Final Examination.

Three Seminar Writing Presentations

Three short in-class writing presentations, three hundred words each, designed to let you display and then analyse your ability to express your critical readings skill in written form. These assignments require you to justify to the class your writing method; receive constructive response from peers and Instructor; and prepare you practically for the Mid-term Essay and Final Essay respectively.

Group Popular Culture Project

A creative project for groups of two that allows you to engage with the present-day cultural context of our course novels. Each group can schedule their presentation on their most suitable available date. Presented in-class, the project will show an example from popular culture--advertising, film, television, etc.--that enlightens and contextualises the course thesis on the differing representations of masculinity and femininity in 20th & 21st century Western society from which our course authors have derived their unique literary engagements.

Mid-Term Essay

A relaxed eleven-week writing path which provides ample time, resources and in-class opportunity to perfect the writing and revision process, in line with the "Writing Intensive" designation for this course.

Final Examination

Open-book Final Examination: Wednesday December 16th 19:00- 22:00, room HCC2245.

Instructor Contact: Office Hours: AQ 6094 -- Tuesday one o'clock to three o'clock, Wednesday in person after class. E-mail to ogden@sfu.ca. Telephone 778-782-5820

Course Approach:

The course will read the books on their own terms, from the axiom that they 'instruct by delighting.' The books share a common characteristic of post-war British novels that focus on maleness or femaleness. Specifically, female protagonists triumph—in terms that are realistic and are her own—where male protagonists experience crises of masculine identity which resolve themselves only after they learn to accomodate diminishment or failure.The arc, that is, of the female-centred novel is upward, but downward for the male-centred novels. The teleology of the course is toward understanding of how the fiction expresses confidence and triumph "....intimately connected to the workings of the society around it." [Peter Keating.]

READING SCHEDULE

September : L.M. Montgomery, Emily of New Moon

Course Wk. 2: L.M. Montgomery, Emily of New Moon

Course Wk. 3: Kingsley Amis, Lucky Jim

Course Wk. 4: Kingsley Amis, Lucky Jim

Course Wk. 5: Stella Gibbons, Cold Comfort Farm

Course Wk. 6: Stella Gibbons, Cold Comfort Farm

Course Wk. 7: Anthony Burgess, A Clockwork Orange

Course Wk. 8: Anthony Burgess, A Clockwork Orange

Course Wk. 9: Helen Fielding, Bridget Jones's Diary

Course Wk. 10: Helen Fielding, Bridget Jones's Diary

Course Wk. 11: Nick Hornby, High Fidelity

Course Wk. 12: Nick Hornby, High Fidelity

Nb: “For purposes of the Class Participation Grade, attendance and punctuality in seminar and at lecture, as well as constructive contributions to discussion, are necessary conditions.

Schedule of Assignment Due Dates

(Assignments coded by colour. See separate assignment posts for details.)

Nb: There is a five percent per day late penalty for all assignments, documented medical or bereavement leave excepted. For medical exemptions, provide a letter from a physician on letterhead which declares his or her medical judgement that illness or injury prevented work on the essay.(The precise word "prevented" must be used in the letter.) The letter must cover the entire period over which the assignment was scheduled and may be verified by telephone.

September 9th, Seminar Writing Presentation #1, in-class.

September 16th: Group Project dates selected.

September 30th, Mid-Term Essay topics posted.

October 7th: Mid-Term Essay peer editing of thesis ¶ or draft outline.

October 14th: Seminar Writing Presentation #2, in-class

October 21st: Mid-Term Essay draft version due in class.

November 4th: Seminar Writing Presentation #3, in-class.

November 4th: Mid-Term Essay draft version returned with comments & conditional grade.

November 18th, Mid-Term Essay peer-editing of preliminary revision.

November 25th, Mid-Term Essay revision due in class.

December 2nd: Mid-Term Essay revision returned with summary comments & final grade

December 16th, Final Examination.

Three Seminar Writing Presentations

Three short in-class writing presentations, three hundred words each, designed to let you display and then analyse your ability to express your critical readings skill in written form. These assignments require you to justify to the class your writing method; receive constructive response from peers and Instructor; and prepare you practically for the Mid-term Essay and Final Essay respectively.

Group Popular Culture Project

A creative project for groups of two that allows you to engage with the present-day cultural context of our course novels. Each group can schedule their presentation on their most suitable available date. Presented in-class, the project will show an example from popular culture--advertising, film, television, etc.--that enlightens and contextualises the course thesis on the differing representations of masculinity and femininity in 20th & 21st century Western society from which our course authors have derived their unique literary engagements.

Mid-Term Essay

A relaxed eleven-week writing path which provides ample time, resources and in-class opportunity to perfect the writing and revision process, in line with the "Writing Intensive" designation for this course.

Final Examination

Open-book Final Examination: Wednesday December 16th 19:00- 22:00, room HCC2245.

Instructor Contact: Office Hours: AQ 6094 -- Tuesday one o'clock to three o'clock, Wednesday in person after class. E-mail to ogden@sfu.ca. Telephone 778-782-5820

Course Approach:

The course will read the books on their own terms, from the axiom that they 'instruct by delighting.' The books share a common characteristic of post-war British novels that focus on maleness or femaleness. Specifically, female protagonists triumph—in terms that are realistic and are her own—where male protagonists experience crises of masculine identity which resolve themselves only after they learn to accomodate diminishment or failure.The arc, that is, of the female-centred novel is upward, but downward for the male-centred novels. The teleology of the course is toward understanding of how the fiction expresses confidence and triumph "....intimately connected to the workings of the society around it." [Peter Keating.]

Mid-Term Essay: Structure

Here is the Writing-Intensive arrangement and the schedule of dates for the Mid-Term Essay, fifteen hundred words and revisions. The assignment is worth twenty percent of the Course grade.

Eleven-week writing path.

Eleven-week writing path.

- September 30th: selection of topics posted on the blog

- October 7th: peer-editing of essay outline and thesis paragraph.

- October 21st: draft version due in class.

- November 4th: draft returned with comments & conditional grade.

- November 18th: peer-editing of draft revision.

- November 25th: revision due in class.

- December 2nd: revision returned with comments & final grade.

- The draft is an opportunity to get your ideas and structure freely down on paper. The marking will identify the types of error which require revision: after studying these you are encouraged to bring the draft to Office Hours for additional and thorough-going help.

- Intensive copy-editing and analysis, in red ink, will be done on the first two-thirds of the essay. The remaining third is left unmarked, to provide you, once having read and studied my work, with a practical document on which to apply the same degree and type of copy-editing corrections yourself. Upon completion of that exercise, you are welcome to bring that to me in an Office Hour for discussion.

- There is a circled grade beside my concluding comments at the end of your paper.

- This is your conditional grade.

- Upon revision of the draught, the mark can go down to the amount of one full letter grade and can go up as much as one full letter grade: conditional upon the quality of your revision.

- If little revision is done, the conditional grade will stand

- If no or poor revision is done the mark will go down.

- If comprehensive revision is done, the mark will go up.

- The mark after the revision will be the final grade for the assignment.

- The revision will be graded according to the improvements made from the draft.

- A complete re-write is possible, if the student feels that they wish to improve upon the range available from the conditional grade received. The complete re-write will be judged as a final revision and the grade on that re-write will be the final grade for the assignment.

Tuesday, September 8, 2009

Popular Culture Examples

Here are two examples from popular culture which exemplify the type of representation of the sexes that our course novels engage with.

Example Two, (American): "Where does he train to take a beating like that?"

- Watch both of these television advertisements.

- Consider how they both represent masculinity.

- Make a choice of one or the other.

- Analyse your selection in detail—frame-by-frame if necessary.

- Prepare a five-minute presentation that makes a strong thesis claim and support that claim with a description of a precise visual or oral component of the advertisement.

Example Two, (American): "Where does he train to take a beating like that?"

Group Popular Culture Project

This creative project allows us to experience the immediate social context in which the novels are written, and see the direct relevancy of the literary artistic genius. The keyword for the project is "enjoyment": the more fun you have with the ideas, the better (ceteris paribus) your result will be.

The project is worth twenty percent of the course grade and thus presumes that each group member will put twenty percent of the course effort into the project: i.e. each project will display 2 X 20% of course effort.

The project is worth twenty percent of the course grade and thus presumes that each group member will put twenty percent of the course effort into the project: i.e. each project will display 2 X 20% of course effort.

- Groups of two will be set course week one

- A trial 'run through' of the project will be done course week one.

- Your group will sign up on week two for your preferred week to present their project in class.

- In line with the information given in lecture over the first two course weeks, your group will look for some aspect of popular culture which shows one of the following:

- enfeebling or disparagement of maleness.

- female dominance or empowerment.

- [Lecture will be considering the efficacy of Charles Darwin's model of maleness and femaleness—centred around the fundamentally performative and therefore necessary uncertain nature of masculine identity—to understand the artistic representations in the course texts.]

- Some aspects of popular culture that you might consider are advertisements, television shows, university course transcripts, public speeches and policies, film, magazines, etc.

- Put together a fifteen-to-twenty-minute creative presentation that informs the class about what your selection from popular culture is specifically saying (the analytic component), and what the significance is for cultural conceptions of masculinity or femininity (the thesis component.)

- Choose a clear and consistent creative format for your presentation. Some possible alternatives are as follows:

- visual and oral presentation

- handouts

- performance (i.e. re-enactment)

- filmed documentary -- on DVD for instance.

- artistic: e.g. a comic book or screenplay.

- etc.

- Choose the mode of your presentation: humourous, polemical, satirical, scholarly.

- Give equal weight to the creative, informative, research and audience-engagement aspects of your project.

- Hand in your presentation materials (e.g. overheads, notes, and similar), and an evaluation sheet and assignment grade will be handed back to your group the week following.

Monday, September 7, 2009

Course E-Mail Netiquette

Here are the points of e-mail protocol for our course :

Here are the points of e-mail protocol for our course :- E-mail (indeed, all communication) between Lecturer and student, and TA and student, is a formal and professional exchange. Accordingly, proper salutation and closing is essential.

- Business e-mail is courteous but, of professional necessity, concise and direct. It rejects roundabout or ornate language, informal diction, and any appearance of what is termed in the vernacular, 'chat.'

- Customary response time for student e-mail to the Course Lecturer or TAs is two to three office days. E-mail on weekends will ordinarily be read the Monday following.

- Use only your SFU account for e-mail to the course Lecturer. All other e-mail is blocked by whitelist.

Missed classes and deadlines are not to be reported by e-mail: if a medical or bereavement exception is being claimed, the supporting documentation is handed in, along with the completed assignment, either in person or to the Instructor's mailbox outside the Department Office.

Course Website FAQ

Here are FAQ about the course website.

- The 5 most recent posts are displayed on the main page.

- A permanent link list, entitled "Pertinent & Impertinent" is always visible on the sidebar of the course website, containing direct links to crucial information.

- Also on the sidebar, always visible, is the "Blog Archive" displaying direct links to all posts on the course website.

- The "Blog Archive" has sections for years 2009 and 2007. Our course links are under the 2009 section. The 2007 archive is for a previous iteration of the course which may, or may not, be interesting for you.

- An "Older Posts" hotlink is always visible at the bottom of the main page which displays the next 5 most recent posts.

- Certain PowerPoint lecture slides are occasionally posted on the course website.

Course Outline

ENGLISH 101W J1.00 Harbour Centre INTRODUCTION TO FICTION

(Writing Intensive)

Instructor: S. Ogden FALL 2009

THE FICTIONS OF THE SEXES: WOMEN’S & MEN’S NOVELS

It is contentious to claim that there are novels for women and other novels for men, notwithstanding publishing and marketing of genre labels such as ‘chick-lit’ and ‘lad-lit’. What is not disputed, however, is fiction’s characterisation of maleness and femaleness. In this course we will read popular and important twentieth-century novels which explicitly configure a male or a female protagonist and which each became notorious for their implied valuation of either the masculine or the feminine. To help frame our understanding of the fiction, we will consider the texts in light of authoritative statements of sexual identity—from Charles Darwin and Sigmund Freud for instance. We will also bring in examples from our own experiences of portrayals of men and women in mass culture. The design of the course uses this particular type of literature as a practical means to learn how to read, analyse and appreciate fiction broadly—part of which involves improving the enjoyable practice of writing.

REQUIRED TEXTS:

Montgomery, L.M. Emily of New Moon N.C.L

Amis, Kingsley Lucky Jim Oxford UP

Gibbons, Stella Cold Comfort Farm Penguin

Burgess, Anthony A Clockwork Orange Oxford UP

Fielding, Helen Bridget Jones's Diary Penguin

Hornby, Nick High Fidelity Riverhead

THE FICTIONS OF THE SEXES: WOMEN’S & MEN’S NOVELS

It is contentious to claim that there are novels for women and other novels for men, notwithstanding publishing and marketing of genre labels such as ‘chick-lit’ and ‘lad-lit’. What is not disputed, however, is fiction’s characterisation of maleness and femaleness. In this course we will read popular and important twentieth-century novels which explicitly configure a male or a female protagonist and which each became notorious for their implied valuation of either the masculine or the feminine. To help frame our understanding of the fiction, we will consider the texts in light of authoritative statements of sexual identity—from Charles Darwin and Sigmund Freud for instance. We will also bring in examples from our own experiences of portrayals of men and women in mass culture. The design of the course uses this particular type of literature as a practical means to learn how to read, analyse and appreciate fiction broadly—part of which involves improving the enjoyable practice of writing.

REQUIRED TEXTS:

Montgomery, L.M. Emily of New Moon N.C.L

Amis, Kingsley Lucky Jim Oxford UP

Gibbons, Stella Cold Comfort Farm Penguin

Burgess, Anthony A Clockwork Orange Oxford UP

Fielding, Helen Bridget Jones's Diary Penguin

Hornby, Nick High Fidelity Riverhead

COURSE REQUIREMENTS:

10% Productive Participation

15% Three Seminar Writing Presentations

20% Semester Group Culture Project

20% Mid-Term Essay (approx. 1500 words with revision)

35% Final Exam

35% Final Exam

To receive credit for this course, students must complete all requirements.

Dividing Post: 2009 from 2007

Posts above this dividing post are for the current (2009) version of the course. Posts below this dividing post are archived posts from the 2007 iteration.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)